Systematic attempts to select athletes based on identification of their special talent are subject to criticism for a number of reasons (e.g., Lidor et al., 2009). The overall problem is simply that talent is so complex a construct that it is not easily defined nor measured. As a consequence of the multidimensionality of athletic talent, some athletes who score low in certain areas are able to compensate with high scores in other areas and reach the international elite level in spite of seemingly bad odds, as in the case of a short basketball player or a tall wrestler. This makes assessing the relevant areas in relation to each other a virtually impossible task (Durand-Bush & Salmela, 2001) and compounds the risk of selecting or de- selecting the wrong athletes.

In addition the fact that most selection models are built on investigations into current elite athletes also means they adopt a static view of the sport. The rapid development of international elite level sport suggests that it is questionable to assume that future demands to excel will match current ones. Below I will cite a couple of findings that show the problems inherent in a talent detection approach.

However we define „talent‟, a number of factors unrelated to it seem to play a significant role in determining the likelihood that a young athlete will make a successful transition to elite sport. One such factor is age. The relative age effect (Helsen et al., 2005; Helsen, Hodges, Van Winckel & Starkes, 2000; Helsen, Starkes & Van Winckel, 2000) highlights birth date as a predictor of athletic success, with athletes born in the beginning of a selection year being more likely to make it to the senior elite level than athletes born late within the selection year. Research has yet to uncover the underlying mechanism, but Côté, Macdonald, Baker, and Abernethy (2006) make a compelling hypothesis that older athletes in a group are likely to be bigger, stronger and faster. This means that they are (1) more often selected for special training and put in decision-making roles, which gives them more time on task, and (2) more often reinforced by coaches, team mates or others in the sense that they achieve success and their success brings congratulation and added confidence. Although likely to be outbalanced during maturation, physical maturity seems to play a role in the selection processes and to define who has access to superior training conditions.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

It has been suggested that there should be a differentiation between talent as raw material and as end product (Gagne, 1985). The proposal involves employing the term “giftedness” to refer to innate potential, defined as untrained and spontaneously expressed natural abilities, and the term “talent” to refer to the superior mastery of systematically developed skills. In consequence of this distinction, and with an eye to soccer, Williams and Reilly (2000b) defined talent detection as the discovery of potential performers not yet involved in the sport, and talent identification as the recognition of current participants with the potential to become elite players. These definitions have the potential to clarify the field, but they have not been widely implemented within talent research in sport (Tranckle & Cushion, 2006).

It has been suggested that psychological factors are of primary importance in determining whether an athlete reaches and stays at a high level (Gould et al., 2002). A number of reviews (Aidman & Schofield, 2004; Morris, 1995; in press; Vealey, 1992) dealing with personality in sport (personality referring to traits in the individual that are consistent across time and situations as well as distinct) identified more than 1500 studies on the subject. This body of research however suffers from a variety of methodological problems ranging from inappropriate sampling, lack of clear definitions of sports participation at the elite level, lack of theoretical basis, to the absence of measurement instruments specific to sport. Morris (in press) concludes that, although individual studies found significant features, this body of research has not been able to establish any common personality factors that reliably distinguish sporting participants from non-participants, participants in certain types of sports from participants in other types, or successful athletes from less successful ones.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

Cultural Psychology

Cultural psychology (Greenfield & Keller, 2004) considers culture and psychological processes to be mutually constitutive. Such a contextualist stand would imply either a holistic position, denying a meaningful boundary between individual and context, or a dialectical position, stating that individual and social world have separate realities but are in constant dynamic interaction (Tudge, 2008). In other words, culture is everywhere in peoples‟ practice, human behaviour is context specific, and the aim of cultural research is to uncover the unique culture of the people under study. This has also been referred to as an emic approach, concerned with what is unique for a socio-cultural context or group (Ryba et al., 2010; Schweder, 1990).

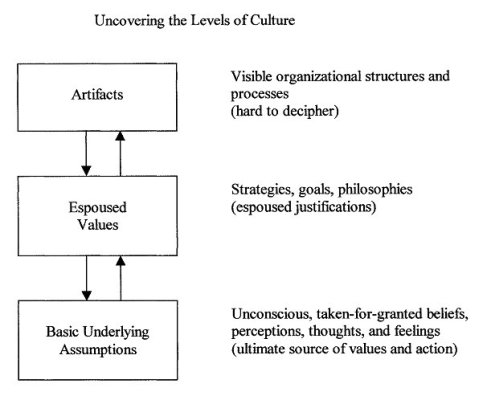

An example of this approach is the study of culture in small groups that has been developed by organizational psychologist Edgar Schein (1992). According to Schein, all groups are faced with two basic tasks. First they must survive and grow through adapting to the constantly changing environment. Second they must keep the group functional through internal integration. Organizational culture emerges as a set of solutions, actions and values that, in contributing to the group‟s ability to solve these two tasks, become integrated to a degree where they are longer questioned. The interactions of the members constantly shape and refine the culture, and at the same time, the culture stabilizes these interactions. Culture is characterized (a) by stability over time, (b) by integration of the key basic assumptions into a „cultural paradigm‟, and (c) by socialisation of new members. Guiding its members in relation to how they should feel, think and act, culture becomes a stabilizing force in the group and serves a basic human need for cognitive stability. Schein‟s notion of organizational culture fits well within a systems theory approach. It focuses on patterns of behaviour that belong to the culture rather than to the individuals and describes the group as an open system constantly adapting to a changing society.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

System’s Theory

Systems theory is not one specific theory but rather a scientific tradition. Systems theory is a term that embraces a diverse set of theories within different areas. These hold in common the idea that most phenomena must be considered systems, that is organised wholes that are so complex that they cannot be disassembled into parts without losing their central quality, or their wholeness (Lewin, 1936).Systems theory incorporates Grand Theories aiming to describe everything from the atom to the universe and to provide an overarching framework for all science (Bateson, 1973; Bertalanffy, 1968), psychological theories (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Lewin, 1936), theories in the field of sociology (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Luhmann, 1995), and in biology (Maturana & Varela, 1987). In applied areas systems theory has been proposed as a basis for working with learning (Bateson, 1973; Luhmann, 1995), family therapy (Minuchin, 1974), schizophrenia (Berger & Milton, 1978), career assistance (Patton & McMahon, 2006) and development of organizations (Schein, 1992).As a consequence of its wide use, systems theory is not a united theory. “One finds wide divergence in definition of systems, in criteria of classification, and in the evaluation of the systemic approach as a contribution to knowledge.”(Rapoport, 1986, p. 1) The section that follows makes no claim to outline systems theory in all its complexity. Instead, some fundamental ideas will be presented that form the theoretical background of this particular study.

The parts of a system interact in complex ways to create a whole, and investigating wholes rather than pieces of the whole is a fundamental notion. This entails an emphasis on ecological validity, on investigating phenomena in their natural context. Investigating specific elements or variables in isolation is considered a reductionist strategy, since isolating a part from the whole may cause it to present itself differently to the researcher. A systems theory approach is essentially interested in investigating systems that are so complex that the researcher cannot isolate specific elements without destroying the whole, the very essence. (Bertalanffy, 1968)

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

GIFTEDNESS AND TALENT

The authors who studied giftedness and talent show us that we cannot continue to conceptualize them as a rare, unique phenomenon that mysteriously sprouts in the body and mind of an individual. So how can we call it? Many terms have been used: “prodigy”, “genius”, “high potential”, “eminence”, “giftedness”, “creativity”, “exceptional ability”, precociousness”.

Over the past 4,000 years, there have been seismic shifts in the ways the phenomenon has been recognized, operationalized, and investigated: from divinely inspired to continuous with extraordinary behavior; from a an expression of profound neurosis to the sine qua non of supranormal functioning; from mysterious and inexplicable to highly accessible, understandable, quantifiable, and replicable.

Changes in conceptualizations of exceptional ability and its accompanying research agenda continue to reflect the combined impact of sociopolitical forces and culturally derived values. To best understand the current perspectives about giftedness we can divide its study in two eras: the prescientfic and the scientific.

In the prescientific era, before the 19th century, beliefs about exceptional ability were grounded in the notion of transcendent abilities. With roots in the writings of the early Greek philosophers, the word genii was first used in the reference to the considerable but not necessarily unique abilities of great artists. Because outstanding artistic performance was thought to be divinely inspired, it was considered to be unknowable and immeasurable.

In the scientific era the study of human biology evolved into a science and the early psychologists espoused the belief that immoderate use of nervous system’s energy, with was genetically predetermined, would result in neurosis. Inclueded in their descriptions of immoderate use were many of the behaviors commonly associated with giftedness and creativity.

During the scientific era, psychometric methods were soon developed to study individual differences.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

Athletic talent development is mainly concerned with the development of the athletes‟ sporting skills and performance and focuses on a limited period in an athlete‟s life. Athletic career development has a broader focus on the lifespan development of the athlete, including the post-sport-career. In a career context, developing an athlete‟s sporting skills is one important aspect among many others, such as balancing sport and life, balancing stress and recovery, and coping with injuries. Put simply, talent development is successful when an athlete manages to transform his or her potential into performance at the international elite level, but career development is successful only when an athlete reaches his or her peak and makes the sporting career a pillar for life in general. In this sense:

Career development is viewed as a broader context for talent development, whereas an athlete‟s talent is considered not only as a set of motor skills and qualities, but also as the ability to develop and effectively use resources to overcome transition demands inside and outside of sport (Stambulova, 2009)

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

Entrepreneurial marketing of sport increases demands on sport development officers to identify talented individuals for specialist development at the youngest possible age. Talent identification results in the streamlining of resources to produce optimal returns from a sports investment. However, the process of talent identification for team sports is complex and success prediction is imperfect.Maturation is a major confounding variable in talent identification during adolescence. A myriad of hormonal changes during puberty results in physical and physiological characteristics important for sporting performance. Significant changes during puberty make the prediction of adult performance difficult from adolescent data. Furthermore, for talent identification programs to succeed, valid and reliable testing procedures must be accepted and implemented in a range of performance-related categories. Limited success in scientifically based talent identification is evident in a range of team sports. Genetic advances challenge the ethics of talent identification in adolescent sport (Pearson DT, Naughton GA, Torode M. University of Sidney).

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment

Say what you think

What is talent? How can we recognize and manage it in young people?

lthough talent detection and development has been the subject of academic study for more than 50 years, definitions have rarely been offered. In the literature “talent‟ refers interchangeably to an athlete’s preconditions for success and to the outcome of the developmental process . Csikszentmihalyi stated that talent is simply a social construction, a label of approval which we place on traits and abilities that are found to be of value to the society in which we live.

The nature-nurture debate is central to a definition of athletic talent. Is a highly skilled athlete gifted by nature with innate talent or with a certain disposition to sporting performance? Or is exceptional performance a result of countless hours of high quality training? Research in the area of athletic talent has evolved away from a focus on the discovery of talent towards an emphasis on the development of that talent, though both approaches tend to focus on the individual athletes.

Howe, Davidson & Sloboda (1998) assign the following properties to the composition of innate talent.

(1) Talent originates in genetically transmitted structures and hence is at least partly innate. (2) Its full effects may not be evident at an early stage, but there will be some advance indications, allowing trained people to identify the presence of talent before exceptional levels of mature performance have been demonstrated. (3) These early indications of talent provide a basis for predicting who is likely to excel. (4) Only a minority is talented, for if all children were, there would be no way to predict or explain differential success. Finally, (5) talents are relatively domain-specific.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

Tags: education, management, sport, young

Welcome to sportpsyco !

Hi everybody, this is sportpsyco, the blog for people who are interested in all psychology applications in sports

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment